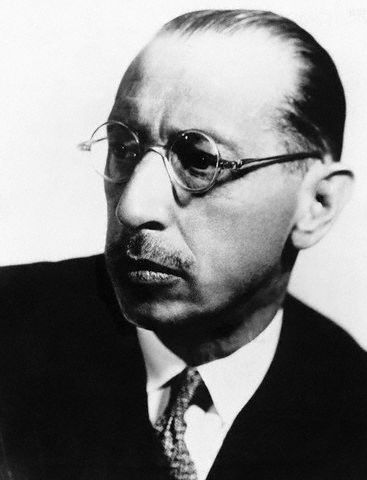

Today in class, we were not discussing our up-and-coming paper (I think it was our journal review, and, being the music major I am, I was comparing two articles on the opera Don Giovanni); instead, we were discussing whether or not one can define "good art." (Random aside...I love semicolons. I kinda do a little celebratory fist-pump when a good sentence featuring a semicolon comes together. I guess I owe that to a friend of mine.) From my professor's perspective, we can judge whether or not art is "good" by comparing it to the standard of accepted material (let's call it the "canon" of art, because that's really what a canon is): for example, we can judge physical art (sculptures, paintings, etc.) by people such as Picasso, Van Gogh, or da Vinci, or music by people such as Bach, Stravinsky, or Mozart, or poetry by people like Frost, Longfellow, Shakespeare, etc. By comparing the material to the accepted standard set by the canon of each field of art, we can determine if it is good. After all, Something gave these artists immortality in some form or another.

I disagreed with her method of defining good art, but I wasn't exactly sure how to put my disagreement into words. The position she held left no room for changes away from the accepted canon, and it left no room for artists whom immortality avoids for one reason or another. Being a musician, I could not help but think of the first time Stravinsky's Rite of Spring was performed: the escape from traditional orchestration and Tonality was so immense that vegetables flew, riots broke out in the theater, and Stravinsky was denounced by the Russian government for being a "decadent artist." Now, however, Stravinsky is revered as the greatest composer of the 20th century, and his works are performed in his memory yearly (I recently saw the Rite of Spring for the first time two days ago - I forgot to breathe for much of the performance).

I disagreed with her method of defining good art, but I wasn't exactly sure how to put my disagreement into words. The position she held left no room for changes away from the accepted canon, and it left no room for artists whom immortality avoids for one reason or another. Being a musician, I could not help but think of the first time Stravinsky's Rite of Spring was performed: the escape from traditional orchestration and Tonality was so immense that vegetables flew, riots broke out in the theater, and Stravinsky was denounced by the Russian government for being a "decadent artist." Now, however, Stravinsky is revered as the greatest composer of the 20th century, and his works are performed in his memory yearly (I recently saw the Rite of Spring for the first time two days ago - I forgot to breathe for much of the performance). Being a young artist myself, and having created (I think) a form of poetry that cannot be compared to any of the great poets of the canon of art, I shrink from the idea that my art cannot be considered good. My form is new, and just like Stravinsky's leaving of tonality, it has the potential to be ignored and even ridiculed for branching off in a new direction. I was at a loss - I knew of no one in the "accepted canon" who supported my views, until I read Rainer Maria Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet for the second time (which, if you haven't read, you simply must), and stumbled across a series of quotes that perfectly illustrated what I was trying to verbalize in class (and contrary to my professor's desires, I will not try to summarize the quotes - I will directly quote Rilke. He says what needs to be said in a tongue far more elegant than mine).

Being a young artist myself, and having created (I think) a form of poetry that cannot be compared to any of the great poets of the canon of art, I shrink from the idea that my art cannot be considered good. My form is new, and just like Stravinsky's leaving of tonality, it has the potential to be ignored and even ridiculed for branching off in a new direction. I was at a loss - I knew of no one in the "accepted canon" who supported my views, until I read Rainer Maria Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet for the second time (which, if you haven't read, you simply must), and stumbled across a series of quotes that perfectly illustrated what I was trying to verbalize in class (and contrary to my professor's desires, I will not try to summarize the quotes - I will directly quote Rilke. He says what needs to be said in a tongue far more elegant than mine).Rilke prefaces his defense of art by saying, "[Art] is not immaculate, it is marked by time and by passion, and little of it will survive and endure. But most art is like that!" Art surviving Time is not necessary? Immaculate art is not necessary? And on I read, wondering if Rilke would mention the Immortal Bards and their accepted Standard, until I saw:

"Even the best err in words when they are meant to mean most delicate and almost inexpressible things."

Ah, even those who maintain a mastery over words that I will never achieve err. Be aware, therefore, dear reader. If the best err, so much more shall you and I. But reading on, I wondered if there is any hope for finding the standard I have been searching for, and suddenly, Rilke spoke directly to me.

"Nobody can counsel you and help you, nobody. Search for the reason that bids you write; find out whether it is spreading out its roots in the deepest places of your heart, acknowledge to yourself whether you would have to die if it were denied you to write. If you may meet this earnest question with a strong and simple 'I must,' then build your life according to this necessity; your life even into its most indifferent and slightest hour must be a sign of this urge and a testimony to it."

Expectantly, I read on, not daring to completely digest what Rilke had just told me, until I found what I was looking for. According to Rainer Maria Rilke, "A work of art is good if it has sprung from necessity."

Must you write? Then do it. Do not worry about the critics; do not worry about the standard. Good art is yours, dear reader. Filled with passion and life, your life, good art is art that you feel you must create. Stravinsky knew this. Rilke knew this.

"Being an artist means, not reckoning and counting, but ripening like the tree which does not force its sap and stands confident in the storms of spring without the fear that after them may come no summer. It does come. But it comes only to the patient, who are there as though eternity lay before them, so unconcernedly still and wide." Sometimes patience is the hardest thing to achieve, especially in art. As young artists, we wonder if what we are creating is worthwhile, and I believe in some senses that worry is justified. We know that there is a canon, and a part of us, large or small, wants to be accepted. But that isn't what truly matters. What matters is that we continue to create, just as those who came before us. Our art may not affect many people, but be assured, your art will have an effect. You may not see it, but it is there.

Practically speaking, Rilke gives two more pieces of advice that I think need to be taken to heart by budding artists such as you and me.

"Read as little as possible of aesthetic criticism - such things are either partisan views, petrified and grown senseless in their lifeless induration, or they are clever quibblings in which today one view wins and tomorrow the opposite." The critics may persecute you and your work, but it is important to remember that they are not the final authority on your art. Perspective is everything.

And finally, "You cannot disturb [your artistic development] more rudely than by looking outward and expecting from outside replies to questions that only your inmost feeling in your most hushed hour can perhaps answer." Live your life in pursuance of Truth first, and then create as our Creator did. Fill your work with your life. You Were Born, your life has value endowed upon you by our Creator, and your art, the expression of that value, is Good.

I guess the moral to this lengthy blog post is this: keep creating. Immortality and fame are both unkind, but unnecessary for your work to be "good art." And be careful how harshly you judge other people's art; do not become the critics Rilke spoke so lowly of: you could end up mocking the next Igor Stravinsky.

Necessary; from the heart,

Not "classic," but apart,

Let heartstrings sing,

Into Immortality spring:

Defining "Good Art."

To Rainer Maria Rilke, for reminding me that I do not create and I am not an artist for fame or immortality.

No comments:

Post a Comment